Barbie and cowboys on canvas

Barbies and cowboys on canvas

The cowboy, that persistent emblem of Western masculinity, chiseled from the attitude of few words, recklessness, and born to the back of a horse. In the popular imagination, he does not bend, and certainly does not break. And yet here, in shades of washed-out rose, grey, and white, the cowboy blurs and dissolves, nearly turning into a ghost. He hovers on the canvas as a remnant of a figure we have so eagerly tried to reshape in our collective vocabulary, a spectral cliché of masculinity that refuses to vanish completely.

My grandfather loved the old Western movies, highlights of Hollywood’s Golden Age. As a child growing up close to him, I was introduced to the world of the Wild West, the prairie, the vast lands where, from time to time, a tumbleweed rolls through the empty streets of wooden settlements, where they meet in the saloon to drink or to start a gunfight. The cowboy was always the hero, usually with a melancholy edge, a lonely figure. They moved with a stenciled ease in their uniforms: the hat, the boots, the tight-fitting trousers. I remember how strange this world felt to me – these men and their attitudes, over-articulated in almost symbolic orders of poses. Observe one, and you knew them all. Even though my grandfather would sometimes laugh heartily, I found little to laugh about.

Only recently did I watch Brokeback Mountain, twenty years after its great success. A classic. Perhaps the film, quietly archived in the back of cultural memory, was always filed for me under a rubric: the unraveling of the cowboy myth, the deconstruction of gender norms. Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal, not without stepping into other clichés (the same as this text might do), manifested the image of the tragically gay love story, foregrounding the brutality of society’s norms. Sobbing boys, fighting their desires and themselves, breaking through concrete walls of suppressed emotions and the inability to speak, act, and be as they feel. It is only the first version of the many new embodiments this archetype has undergone ever since.

The ideals of Western culture (historically questionable not only because of the role models they postulate) became infantilised figures, characters we can slip into like costumes, or deny altogether. The cowboy, red-eyed and wasted, seems exhausted by his role. Tired of being what the world expects him to be, he might whisper: Let’s leave it behind. Let’s leave this stage. Let’s disappear. Thus, are we witnessing the transformation of a heroic archetype into its tragicomic dissolution, or into a moment of humanization (the two are not mutually exclusive)?

An archetype is a blueprint, a primal image or symbol that surfaces across countless forms of representation. Archetypal figures inscribe themselves into our collective consciousness. Carried across generations, they appear as myths and literary motifs, as well as stereotypes and everyday clichés. Here they are painted as though they were wax figures: stiff, tall, doll-like. Do they invite us to identify with them? Perhaps not. They seem to refuse that moment and yet their exposed fragility, their hollowness, their ghostliness leave us in a liminal space of negotiation.

Barbies and cowboys on canvas, they are slowly colliding. Is it parody or confession, critique or self-examination? Is the gesture one of mockery, or of tenderness? Perhaps it is an attempt to deconstruct, to re-stage, to ask again what it means to inhabit these forms that both shaped us and continue to haunt us.

Text by Sophie Fitze

Oilpaint on canvas 170 x 110 cm

Oilpaint on canvas 110 x 170 cm

Oilpaint on canvas 110 x 170 cm

Oilpaint and aquarelle on canvas 100 x 240 cm

oilpaint on canvas 100 x 240 cm

photographs by Julien Jonas

Screens

In this video installation, an alienated landscape features two screens mounted on mountain-like structures. On the screens, a pair of lips appears, producing sounds that represent different body parts, such as plump hands or long legs. The installation creates a surreal world where everything revolves around body fetishism, reducing the human form to fragmented desires and sensual symbols.

Pictures Screens by Julien Jonas

JONGENS DIE PROBEREN TE WENEN

JONGENS DIE PROBEREN TE WENEN

ELIAS DRIESEN

LUCY, PEAKS

RUE BORDIAU 15

18 OCTOBER, 2024

At number 15 in a street on the edge of the European Quarter. A Friday evening. Tired footsteps gather, lighten up and head towards a market. The weather is mild.

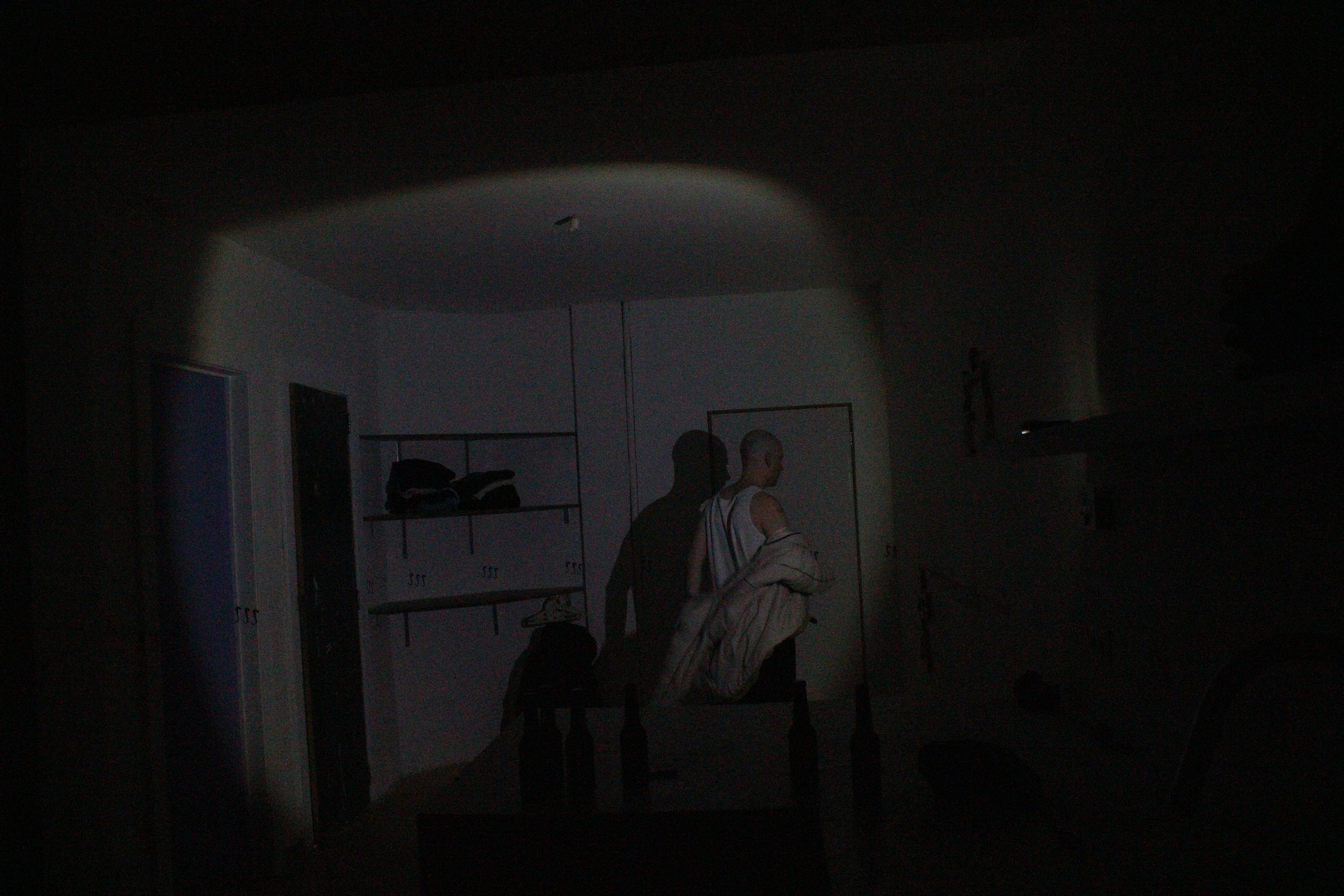

Lucy, peaks opens the pigeon-blue door of a bourgeois house. I bend down to go through the service entrance. It's dark. Three rooms in a row. The first with bikes, the second, a kitchen, the third with a table and a view of a city garden. The position, on the entresol, means that my gaze is at the level of the grass. I look up to see two young men sitting on a bench on the left-hand side. One bald with a suit and tie (the artist), the other in black with high lace-up shoes (his brother).

Silence except for a BOSE loudspeaker placed on the table. From it I hear the sounds of the outside world. Very distinctly, including the quiet of the indoor island. The rectangular window frames the stage and separates the darkness inside, where I'm standing, from the fading light of the garden. The two individuals are rubbing and scratching painted wooden objects. These objects, previously laid out on the grass, remind me of Ola's Racket ice-creams, which the artist has already painted. Others saw them as baby bottles or condoms. These variations lead to different interpretations of the nature of the relationship between the two men. There are few clues. Interaction is minimal. The man in black is absorbed in his telephone and the bald man seems lost in his world of princes, swans and unshed tears.

The performance, in a loop, includes a sequence:

- In the kitchen. The man in the suit enters first and leans against the sink. Illuminated by his mobile phone, he listens to a recording of what seems to be him crying. Not loud sobs, but delicate, liquid moans. Why is he listening to himself? Is it a way of helping himself to cry again? It’s not working. The man in black enters and also leans against the edge of the kitchen, but on the other side. He turns on the cooker hood light and plunges back into his phone. Does he lack empathy? Or is he used to the presence of this melancholic person in his kitchen?

- In the garden. The man in the suit is kneeling, pressing his mobile phone against the window. On the screen, a video of his silhouette behind the fogged-up glass of a shower. Naked, he removes the mist. The sound of rubbing against the glass can be seen through two other windows, that of the telephone and that of the window;

- In the garden. The artist is lying down with his head raised. At various intervals he stammers out the phrase ‘boys who try to cry’, and each time the loudspeaker emits pre-recorded 80s-style laughter;

- In the garden. The two men hug. The only moment of contact. A succession of embraces, with the microphones transmitting the shock of the chests. Tender and virile at the same time. Especially that hand that gently caresses the back of one of the companions;

Restrained. Words and tears have a hard time coming out. I am drawn to the artist's stammering over his swan, which changes from ‘the swan’ to ‘the one’ and is both ‘with no fears and no tears’ and ‘with fears and tears’. The vulnerability of a man in a crumpled suit. The insouciance of the young man who moves effortlessly from his screen to a tender embrace and then picks up the wooden objects. No questions asked.

The interplay of screens, windows, microphones and recordings seems just right. An intimate peformance but at a respectful distance from us and the artist. And then there's the warm beauty of the outside sound that comes through so clearly in the darkness of the house. An aerial soundtrack of birdsong, nightfall and planes taking off. We stay on earth with the kitchen’s extractor hood, the recorded laughter and the omnipresence of the telephone screens.

The young man in black with his high shoes and his German-Slavic name, Anton, takes me back to the last century. To when this house must have been built, in the rural hills north-east of Brussels. I'm reminded of Hermann Hesse's book ‘The Steppe Wolf’, and the story of Harry Haller, torn between his melancholic, solitary personality and his desire to belong to bourgeois society. Elias Driesen's duet is a reference to the double, but more as the expression of a brotherly friendship where the ‘weaknesses’ of the other - addiction to mobile phones or tears - are accepted without drama. Anton and Elias, Elias and Anton. The plural of the title indicates that both are trying to cry. If it's obvious for one of them, for the other it's harder to imagine what's behind his silence and casualness. Who needs to cry more?

Post Scritum I

The performance took place in my house, but this evening I felt like a spectator like any other. I was welcomed into a place that was no longer entirely familiar, with the artist's own energy and unusual sounds. I attended all the rehearsals (of which there were many!) but I plunged back into the basement, feeling that delicious sense of strangeness all over again.

Post Scritum II

Lucy, peaks. What a fine group of people. Pampering the creative energy of a friend while providing invaluable logistical/material/human support (lighting, sound, visitor reception, communication, documentation). Their choice of unusual locations awakens something in me that's different from the usual exhibition venues. Curiosity and the joy of occupying public and private spaces. Especially when a crowd gather on a peripheric pavement that's usually so calm.

Roshan Di Puppo

text written by Roshan Di Puppo for EACHBXL

Pictures jongens die proberen te wenen by Amel Omar

little struggle #2, I would be a jacket, Keep up with the sample tracks. / collaboration with Nello Margodt, 2024

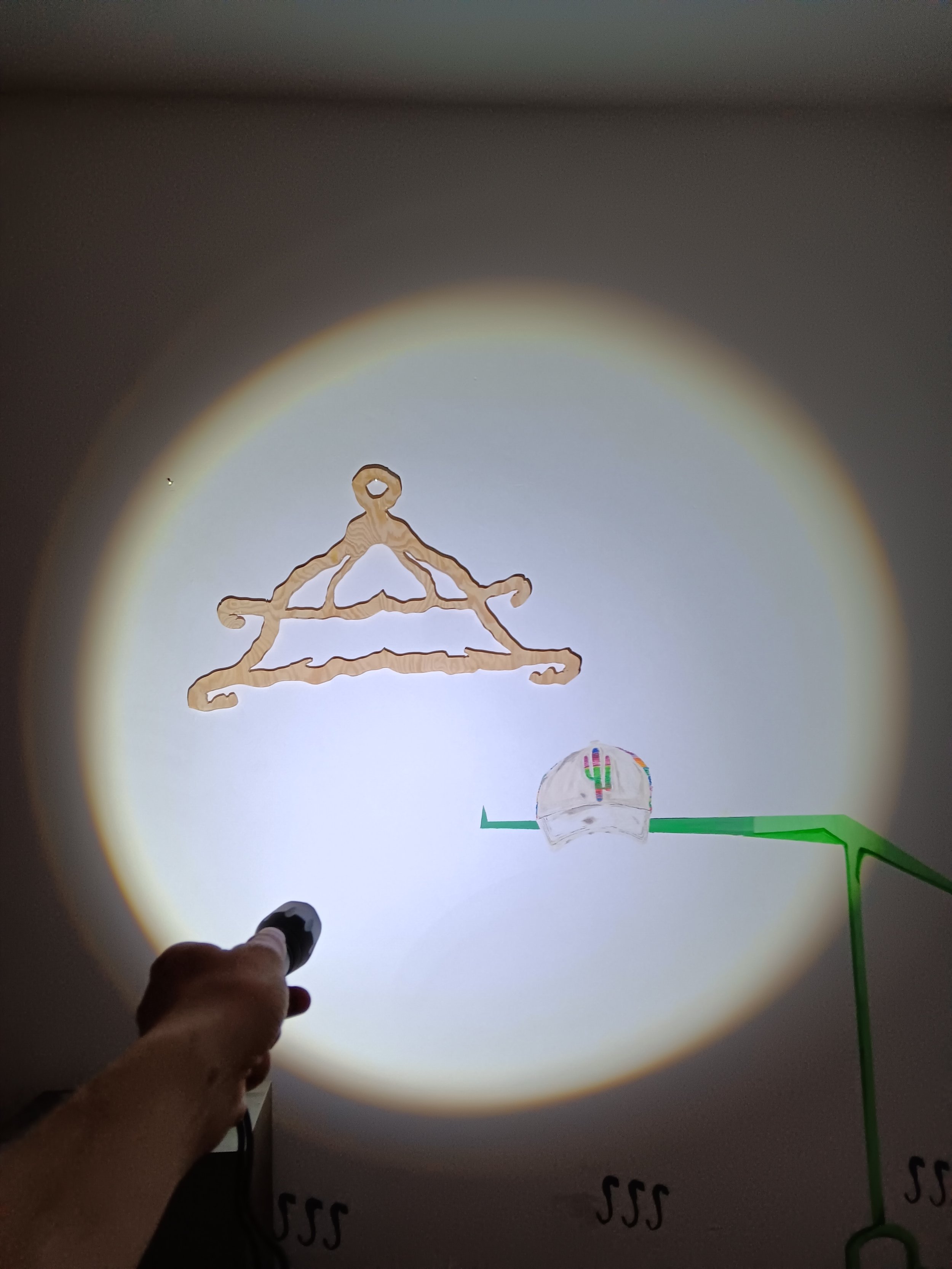

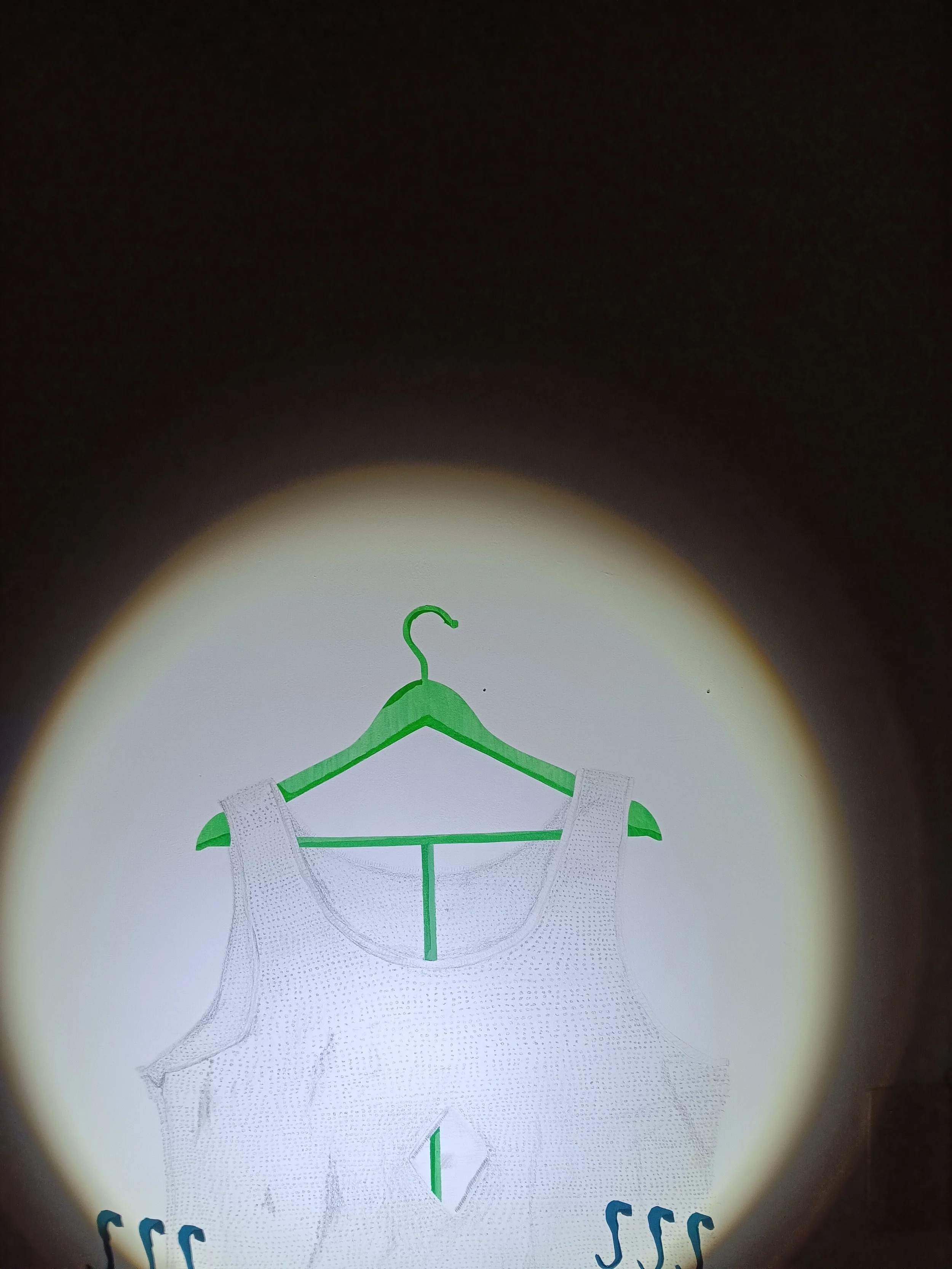

In this performance/installation, I collaborated with Nello Margodt. We each have different conceptual views on what happened. The exhibition centers around clothes. As you move through the living room, you’ll see my favorite pieces of clothing drawn on the wall. Nello created coat hangers specifically for these drawings. For me, this series is about exploring my masculinity, simply questioning it—nothing more. The installation was accompanied by a performance in which we theatrically explored the actions we take with clothing: how we wear it, fold it, hang it, and so on.

It is the cake you should get a bite out. You shouldn't try to bite a shark. You should try to kiss a girl. A bite out of the shark is less satisfying then a bite out of the cake. The jawline of the shark is impressive. Like the jawline of a girl can be. The cake doesn't have a jawline. The cake makes your jawline. The toppings are yours. But do not choose the toppings out of necessity. Choose it because of wat the topping is. Not wat the topping should be. The topping you should be, already has been decided. Like the shark is decided. You shouldn't bite the shark. You should try to kiss the girl. And try to bake the cake.

Judgy Judgy Judge, 2021

In this installation/performance, I question the current form of juries. I do this through the recitation of a poem that I have specially written for this occasion. In the poem, I explore the role and functioning of juries and the impact they have on the individuals and works being judged. With this recitation, I hope not only to raise critical questions about the functioning of juries but also to start a dialogue about possible alternatives or improvements in the way assessments are conducted.